Why Traditional Safety Programs Cannot Achieve Continual Improvement

Even with the extensive knowledge professional safety management has accumulated about accident prevention in the last 100 years, the evidence shows safety programs still can be woefully ineffective. Unfortunately, there are numerous examples of this reality: the Challenger and Columbia accidents, the Sago and Massey Mine accidents, BP’s Texas City Refinery explosion and its Deepwater Horizon disaster and the fact an average of almost 5,000 people are killed and millions more are injured on the job each year.

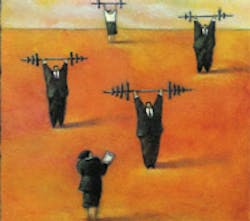

Investigations of these tragic events reveal a common problem: Even though management claims a commitment to operate safely, the real or imagined pressures of production can defeat any safety program. The reason is that safety is a requirement for a company, not an objective. This can lead to companies failing to deliver on safety when it is needed most, with employees paying the severest consequences.

The primary reason for this failure is management’s misplaced emphasis on two areas of safety management. They are:

➤ The effort of the safety department to ensure the company complies with safety specifications, rules or regulations and

➤ Management taking steps to motivate people to behave safely.

These two things are driven by management’s embrace of traditional safety programs in which compliance is enough. Unfortunately, emphasizing only regulatory compliance and motivation programs will not contribute to the overall effectiveness of any safety program. In fact, they actually can help prevent continual improvement of safety performance.

Transformation

Since the 1970s, American corporate management has been undergoing a transformation. Mass production, with its mind-numbing, boring and repetitive job duties, is being replaced with production systems developed by Japanese companies that focus on high quality and low cost. Now, quality is the key to survival, giving companies a competitive advantage.

To meet the challenge issued by Japanese manufacturers, American management first tried to reform its command and control system. This was problematic because when you reform a system, you leave it alone but try to change the outcome by modifying the means it employs. (Do the same thing in a similar fashion only better.)

American managers did this when they tried to copy initiatives pioneered by Japanese companies – such as quality circles – and thought that would fix their problems. This approach failed miserably. They didn’t realize they had to transform their whole management system.

When you transform a system you change its objectives or its ends. They had to change their quality objective from being able to only meet specifications to continual improvement so they could reduce variation in the system. The two ways of managing have nothing in common with each other and cannot be reconciled. American companies have struggled to make the transformation and some have made great strides in staying competitive in the new economy but many have not.

The surviving companies now work to deliver high-quality products and services at lower costs. Their management knows operations must be lean to be competitive and seeks to eliminate or reduce anything in production that does not add value. This requires involving every employee in improving all parts of the system. Companies now tap the mental labor of their work force at all levels to help solve quality and productivity problems. Gone are the days when meeting specifications was the ultimate objective for good quality.

Being able to produce high quality products still isn’t enough, however. These companies realize the management system also must be innovative and creative when it comes to taking care of their customers with a quality product. (Think Steve Jobs and the iPhone.)

But while management’s fundamental theory and thinking about quality has been transformed, the same cannot be said about safety. There has been no external force to challenge the safety management system similar to what happened to quality. Consequently, safety managers are content with reforming, rather than transforming, the safety process. They do this by tweaking the means of delivery of safety through the hiring of personnel, safety training, safety inspections and audits, accident investigations, safety motivational schemes such as coaching employees and incentive programs to change unsafe behaviors.

These efforts may make managers feel good, but they cannot deliver continual improvement. Their primary objective is to maintain the status quo, not to improve things. They have nothing to do with removing common causes (faults) in the work system that are responsible for most accidents.

The most glaring example of a corporate management that is content with reforming rather than transforming safety is BP. Five years after the Texas City blast in which 15 people were killed, a similar story of ignoring safety and cutting costs to maximize profits emerged from the Deepwater Horizon explosion in which 11 workers were killed. As a result of the Deepwater tragedy, BP has promised a new division-level safety unit with sweeping powers to meet safety specifications. BP’s approach to solving their problem is like rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic.

Traditional safety management talks about empowering workers as though management distributes its power as it deems necessary. Basically, employees are asked for input on some safety matters but the final decision on how things will be done is left in the hands of management.

By focusing on successful compliance and shaping employee behavior, traditional safety cannot deliver continual improvement. At its best, it only can maintain the status quo.

In today’s economy, businesses are challenged to continually improve quality and they do it. At these companies, the most important thing an employee can do is share his or her knowledge about eliminating daily problems with quality, productivity and safety in the system. Knowledge always is given voluntarily, so the de-motivating methods practiced in command and control will not work in this new environment. This is as true for safety as it is for quality.

Traditional safety management is effective but nowhere near what it could be if it adopted the management theory of continual improvement. To do this, it would have to change its objectives from compliance and employee motivation to continual improvement of safety in the work system.

In this world, safety management must be fast, focused, flexible and friendly to address the variations in common causes in the always-changing processes created in lean work systems. Safety management must create a system in which employees experience autonomy, mastery and purpose when it comes to on-the-job safety. These three concepts are absent in traditional safety management and this prevents ownership of the safety program by employees, a step that is necessary for any safety program to be effective.

Thomas A. Smith is president of Mocal Inc. He can be reached at [email protected] or 248-391-1818.