Let’s Make Workplace Safer by Moving Forward, not by Looking Back

In the film “Midnight in Paris,” the male lead, Gil Pender (played by Owen Wilson), travels back in time to the 1920s, where he meets famous authors, artists and critics, among others in France’s capital city. It’s a film about nostalgia and the glory days, and it’s glorious.

The costumes and sets are spectacular, and the all-star cameos (Kathy Bates and Adrien Brody, to name a few) makes the film a joy to watch. But it’s twist near the end that makes this movie one of my favorites. Gil's crush from the 1920s, Adriana (played by Marion Cotillard), tells Gil that if she could travel in time, she would go back to Paris’ golden age: the 1890s.

Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about the past. I understand the lure of longing for days gone by, especially those that our memories have cast with a soft light. Nostalgia is a powerful emotion, but memories are often fickle.

We remember only the best parts, like how romantic the late 18th and early 19th centuries were. Indeed, that was when the likes of Lord Byron, William Wordsworth, John Keats, Mary Shelley and Jane Austen were producing their masterpieces. However, there were also the deadly Napoleonic Wars and typhus, cholera and smallpox outbreaks, among others.

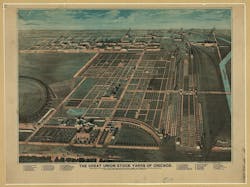

It was with that critical eye that drew me toward my first ever reading of Upton Sinclair's The Jungle. I wasn’t sure I’d have the stomach for Sinclair’s fictionalized story based on his time spent working at a meatpacking plant in Chicago’s Union Stock Yards. Although I had to refrain from reading right before or after eating, it’s one of the best books I’ve read all year.

Sinclair’s book focuses on the working conditions for protagonist Jurgis Rudkus and his family. Jurgis and the other adult family members worked in factories for at least 12 hours a day, six days a week—including Christmas. Initially, the adults wanted the children to attend school, but when financial circumstances worsened, they had a priest forge a certificate so the children could contribute to the household. While fictional, the characters represent the real plight of the many immigrants and former slaves who came to the Stock Yards looking for a chance at the American dream.

The author’s gruesomely detailed descriptions of food manufacturing processes make me grateful that I needn’t drink pale-blue milk, watered down and doctored with formaldehyde. Or that I needn’t eat sausage treated with borax and glycerin and full of “potato flour,” or the remnants of potato after the starch and alcohol have been extracted.

The working conditions at the meatpacking plant where Rudkus and others butchered meat for hours a day without gloves, goggles or other personal protective equipment (PPE) were even worse.

It's no wonder that Sinclair’s story was so riddled with so many references to characters suffering accidents, injuries, illnesses, diseases and infections, such as blood poisoning (also known as the life-threatening condition sepsis).

It’s also no wonder that Sinclair’s story prompted nationwide outrage.

Publication of Sinclair’s seminal work—in serial installments from February through November 1905 and then as a book in February 1906—is credited with breaking through the logjam for the pure food movement.

On June 30, 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt signed two pieces of legislation that established the first federal food safety laws in America. The Meat Inspection Act set sanitary standards for meat processing and prohibited companies from mislabeling or adulterating their products. The Pure Food and Drug Act created the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and prohibited the manufacture or sale of misbranded or adulterated food, medicines and liquor in interstate commerce.

Sinclair’s story does not make me nostalgic for bygone days. I’ll happily take all the PPE, technology and training you want to give me to be safe on the job, thank you very much.

For me,The Jungle marks the intersection of past, present and future. As far as I know, workers have always wanted to do their job and then go home to their family. Workers have always wanted to have a belly full of food and a clean and comfortable home. Workers have always wanted to practice or pursue activities that are important to them, such as involvement with their faith community or gardening. I have never heard workers say they want to do their job more dangerously or that they wouldn’t mind being injured, maimed or killed to support their company’s bottom line.

Some things change, and some stay the same. But as safety professionals—and as a society—we should not fool ourselves by thinking the past is always better. Much of the time, we stand on the shoulder of previous generations’ accomplishments. That is the idea that helped build America, after all.

With that in mind, let's not spend more time debating, or limiting, the scope of occupational safety and health. Let’s not treat workers as expendable labor rather than as complete people who need psychological safety and be their authentic selves to perform their best. Let’s stop focusing on historical data.

Instead, let's focus on how to intervene even before a near-miss incident. Let’s allow our desire to leave our children and grandchildren a better world guide today's efforts and decision-making.

I’d like to propose an alternative—and quote one of my favorite songs: “The best is yet to come and babe, won't that be fine? You think you've seen the sun, but you ain't seen it shine.” Let’s let the promise and potential of better, brighter days ahead inspire us to do more, starting right now.

Nearly ever description from Sinclair's novel seems to get worse and uncover new levels of depravity. Here are a few excerpts:

“There was not even a place where a man could wash his hands, and the men ate as much raw blood as food at dinnertime. When they were at work they could not even wipe off their faces—they were as helpless as newly born babes in that respect; and it may seem like a small matter, but when the sweat began to run down their necks and tickle them, or a fly to bother them, it was a torture like being burned alive.”

"Under the system of rigid economy which the packers enforced, there were some jobs that it only paid to do once in a long time, and among these was the cleaning out of the waste barrels. Every spring they did it; and in the barrels would be dirt and rust and old nails and stale water—and cartload after cartload of it would be taken up and dumped into the hoppers with fresh meat, and sent out to the public's breakfast. Some of it they would make into 'smoked' sausage—but as the smoking took time, and was therefore expensive, they would call upon their chemistry department, and preserve it with borax and color it with gelatine to make it brown. All of their sausage came out of the same bowl, but when they came it wrap it they would stamp some of it 'special,' and for this they would charge two cents more per pound.

"There were the men in the pickle-rooms, for instance, where old Antanas had gotten his death; scarce a one of these that had not some spot of horror on his person. Let a man so much as scrape his finger pushing a truck in the pickle-rooms, and he might have a sore that would put him out of the world; all the joints in his fingers might be eaten by the acid, one by one. Of the butchers and floorsmen, the beef-boners and trimmers, and all those who used knives, you could scarcely find a person who had the use of his thumb; time and time again the base of it had been slashed, till it was a mere lump of flesh against which the man pressed the knife to hold it. The hands of these men would be criss-crossed with cuts, until you could no longer pretend to count them or to trace them. They would have no nails,—they had worn them off pulling hides; their knuckles were swollen so that their fingers spread out like a fan. There were men who worked in the cooking-rooms, in the midst of steam and sickening odors, by artificial light; in these rooms the germs of tuberculosis might live for two years, but the supply was renewed every hour. There were the beef-luggers, who carried two-hundred-pound quarters into the refrigerator-cars; a fearful kind of work, that began at four o’clock in the morning, and that wore out the most powerful men in a few years. There were those who worked in the chilling-rooms, and whose special disease was rheumatism; the time-limit that a man could work in the chilling-rooms was said to be five years."

"It was a sweltering day in July, and the place ran with steaming hot blood—one waded in it on the floor. The stench was almost overpowering, but to Jurgis it was nothing."

About the Author

Nicole Stempak

Nicole Stempak is managing editor of EHS Today and conference content manager of the Safety Leadership Conference.